Surging Household Formation and Falling Rent Growth: Housing Demand and Its Impacts

As experts from across the multifamily industry speculate on the performance of the apartment market in 2023, researchers at the Harvard Joint Center of Housing Studies examine the causes behind the record household formation during the pandemic, with pointed implications for housing demand in years to come.

GlobeSt: How Far Will Apartment Rents Fall This Year?

This is the world we’re living in right now. The headline is “How Far Will Apartment Rents Fall This Year.” Not rise, but fall. It’s not even “Will Apartment Rents Fall This Year,” they’ve assumed falling rents, and now we’re asking how much. Great attention-grabbing headline, but none of the sources in this article are predicting rent growth.

But, really, to repeat myself, this is the world we’re living in right now. The current slide in rent growth is such that, even if this headline doesn’t match the content of the article, it’s certainly what people are thinking about right now. So, given this atmosphere of negative expectations, how nice is it that we could see around 3% rent growth next year? Not so bad, right?

Greg Willett of Institutional Property Advisors predicts 3.1% rent growth in his best-case scenario.

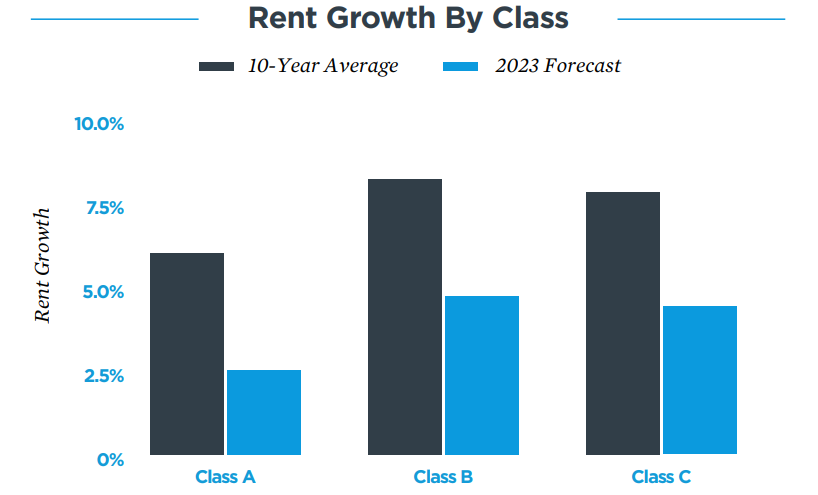

Willett says that we’ll see the strongest growth in middle-of-the-road Class B properties and some in Class C, but there will be challenges for Class A properties that are competing against newly-built apartments in the same area.

As Willett describes it, these challenges are an outgrowth of new supply and not due to falling off demand for luxury apartments. To repeat something we’ve noted previously, apartment supply is going to be different in each and every market, and if you’re investing in a Class A apartment in a sub-market with little-to-no new supply coming online, there is going to be much less risk of poor performance.

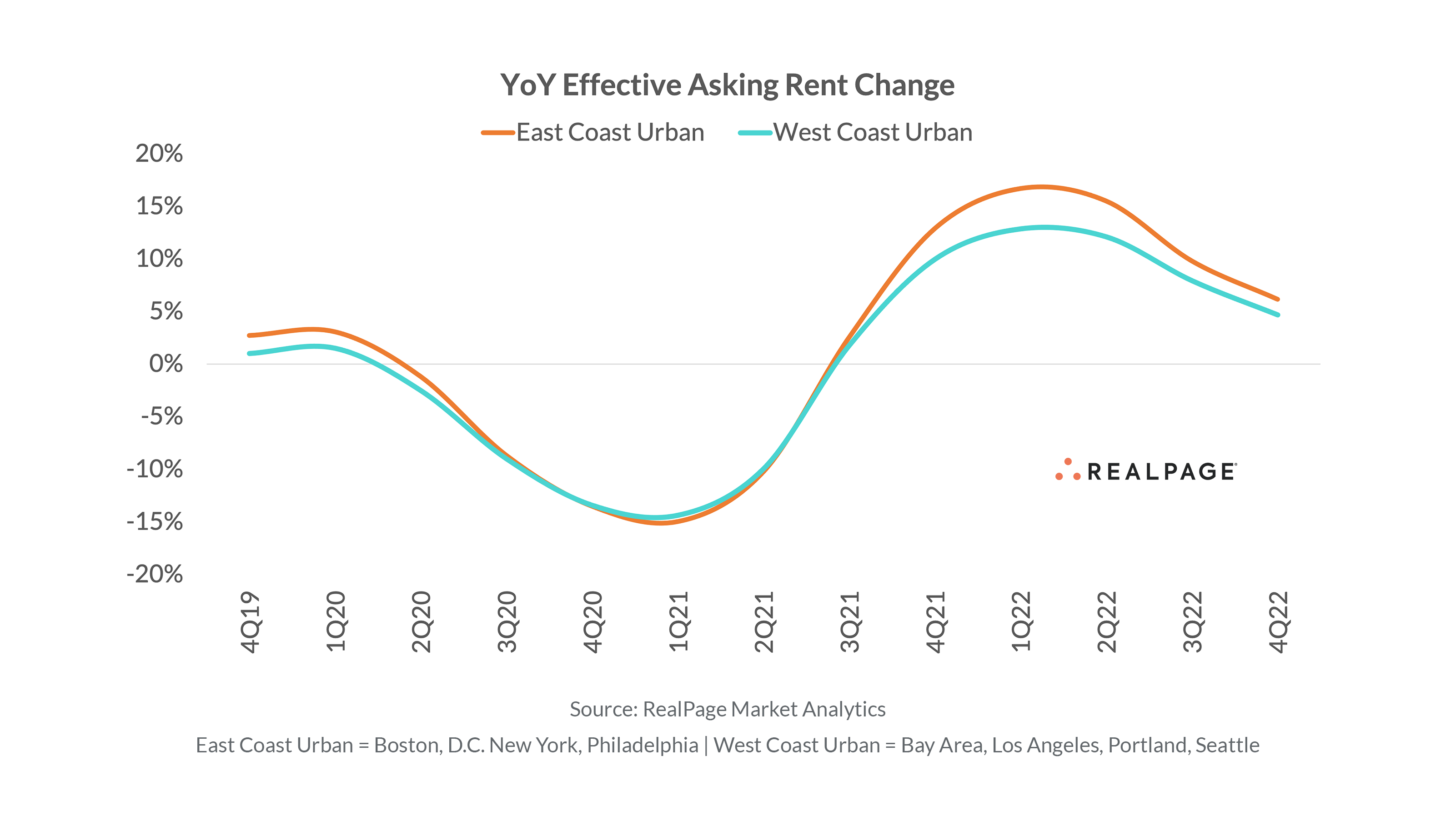

The next multifamily researcher cited, Jay Parsons of RealPage, didn’t provide a specific number but did have some insights about asset classes and submarkets that complement Greg Willet’s

Like Willet, Parsons sees Class B as the most promising asset class, specifically, suburban Class B.

Parsons also sees some challenges for Class A properties, specifically those downtown. Looks like we’re not going back to the central business district just yet, but I’ll be interested to see how these city vs. suburb trends play out.

Sure, remote working is going to stick around, but how much remote working is going to stick around?

Yes, more Millennials are entering the age where other generations were buying homes and starting families, but have attitudes toward homebuying changed at all? 2008 surely changed some minds about buying a home, and with average mortgage payments still quite, quite high, homebuying has not exactly recaptured the hearts of Millennials in search of housing.

Next we’ve got Yardi Matrix, with a prediction of 3.1% rent growth for 2023. Is this the same as Greg Willet’s 3.1%? No! Willet’s number was his best-case scenario, so maybe he was thinking 2.5% as the most likely rent growth number.

Yardi Matrix projects lower growth through the Spring that picks up in the Summer of this year, with rent growth impacted by prevailing economic conditions in 2023.

Yardi Matrix researcher Andrew Semmes does add that they expect a late Q3-Q4 recession to dampen rent growth, but not enough to wipe out all of the rent growth gains from the first part of the year.

So, we’ve got some asset type insights from Greg Willet, some sub-market trends from Jay Parsons, and Andrew Semmes and Yardi Matrix brings us some timing predictions.

To return back to my comments about the headline of this article, it may seem like falling rents is the only possibility, but none of the multifamily experts here are saying that rents will fall at all. And in each one, there are brighter spots than others. Look, it’s not going to be as easy as finding the asset type that Greg Willet likes, the right sub-market from Jay Parsons, and the best timing from Andrew Semmes, but again, these are not doom-and-gloom predictions. This could be as close to historical norms for rent growth as we’ve seen in the past three years.

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies: The Surge in Household Growth and What It Suggests about the Future Of Housing Demand

This report is an important one because it deals with a metric that sits pretty close to the heart of housing demand: Household formation, or as they are measuring it here, household growth. This is the number of new households that form each year in the United States. Maybe it comes from people moving out of their parents’ homes, maybe a new family immigrates into the country, or maybe a struggling grunge band finally gets a record deal and they’re each able to get their own place now.

Household formation is particularly relevant now because there was an unusually high increase during the past few years that markedly outpaced expectations. So, if we had a few years of very high household formation in the past few years, does that mean that we are going to have a few years of very low household formation in the next few years?

Figuring out the reasons behind this increase in household formation is going to be key to determining the strength of housing demand in the years to come, and that’s what this report sets out to do.

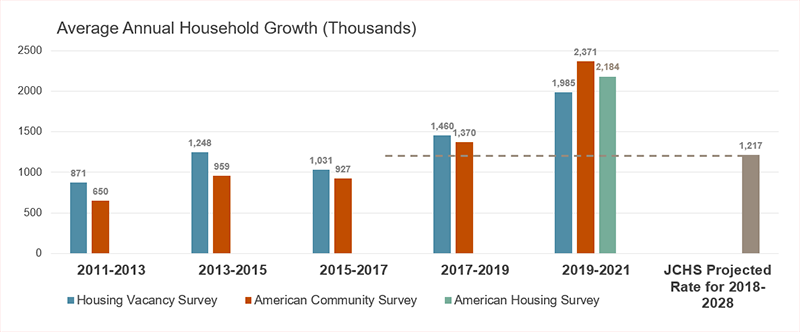

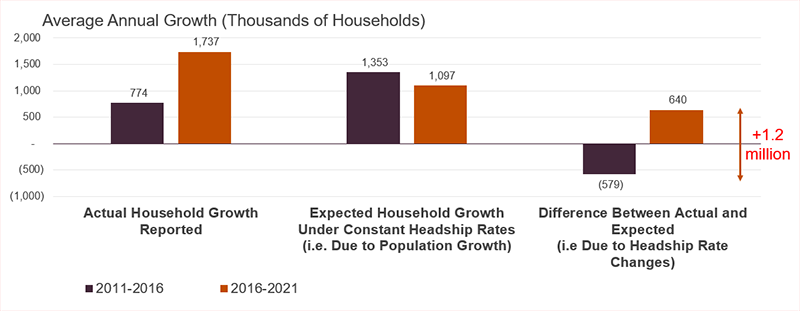

To get into specifics, in 2018, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies predicted that household growth in the next ten years would be about 1.2 million each year on average. They were not correct.

Even the 2017-2019 pre-pandemic average ended up around 1.4 million annual growth, and the numbers for 2019-2021? Way above the 1.2 million prediction. From about 2-2.3 million household growth, depending on the source.

So, the prediction from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies was not correct, and who better than the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies to figure out why household formation surged ahead of their expectations?

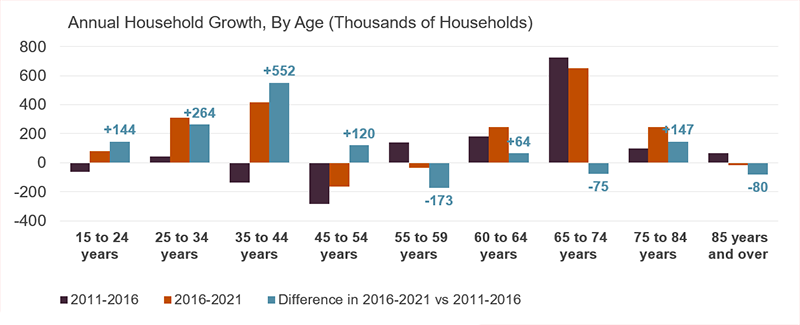

It’s not a huge surprise that Millennials were the age group with the largest growth in household formation.

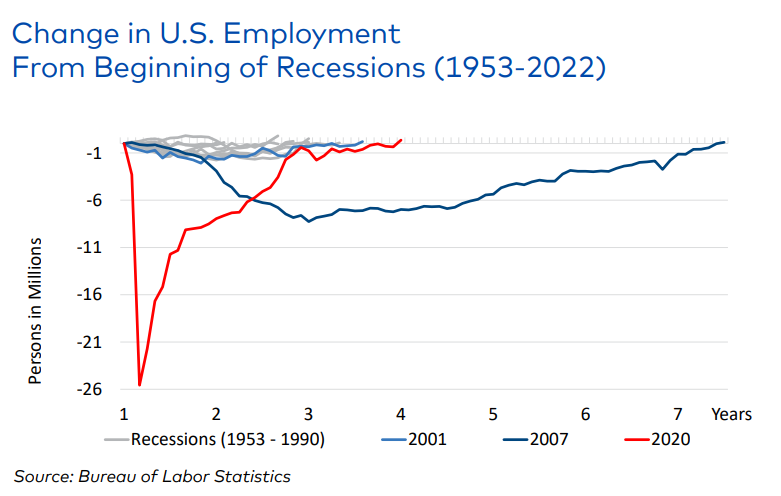

Here come the first two reasons behind the increased household formation (I’m grouping them together as one reason): economic factors like 4.9% wage growth in 2021 and an unemployment rate that dropped from 6.7% to 3.9% in 2021. I think that the wage growth factor is the big one here considering that the unemployment rate was falling from that initial COVID spike.

Between 2016 and 2021, the amount of household growth in the 25-34 cohort and the 35-44 cohort was about double what it was in the previous five years.

“Such a pickup in growth in this age group cannot be explained by growth in the underlying population alone, and suggests older millennials were now forming the households that had been delayed earlier in the decade.”

There’s reason number two: “years of pent-up demand for new households,” which was unlocked by the favorable wage and employment situation. This pent-up demand factor is interesting, but I wonder, when they were making their 2018 prediction that underestimated household growth, how much they were aware of the pent-up demand that they cite as such a powerful driver in their new analysis.

Finally, reason three: increased headship rates. This is increased household formation that is due not to population growth but due to situations like that grunge band I mentioned earlier: People who were previously roommates now are renting or buying their own respective homes.

The fact that so much of the increase in household formation came from increased headship rates, “suggests the current surge in household growth is temporary” because we’re reaching the foreseeable peak of headship rate right now. Like, all of the roommates have already gone and gotten their own places.

Given that the other driver of household formation, population growth, is very low right now compared to historical averages, then, as the JCHS argues, we could be seeing lower housing demand such that “the impact on markets could be significant.”

I’ll offer a gentle redirection that may steer markets away from such a significant impact: The report says that there’s no more room for increased headship rates, that all of the roommates have already moved out of their shared apartment and gotten their own places. But I think that there are still some roommates left.

JCHS says that we have recovered a great deal from the post-2008 housing slump, with headship rates up to 2011 averages, but in 2006, the pre-housing crisis headship rates look better than 2011. If we set 2006 as the peak, then we are a little past the halfway point of increasing headship, which is to say, housing demand could still have room to increase, and the story is not over yet.